Manchester College and the Second World War

Manchester College Oxford and the Second World War

Ashley Jackson and Kate Alderson-Smith[1]

In 1938 the Vice-Chancellor and Registrar, in conjunction with government authorities, devised a plan for the take-over of University and college buildings in the event of war with Germany. About half of Oxford’s colleges were earmarked for requisition by departments of state and the armed forces. Those in the other half were designated ‘reception’ colleges, and would be used to accommodate the people and carry on the teaching activities displaced by the requisition of their counterparts.[2]

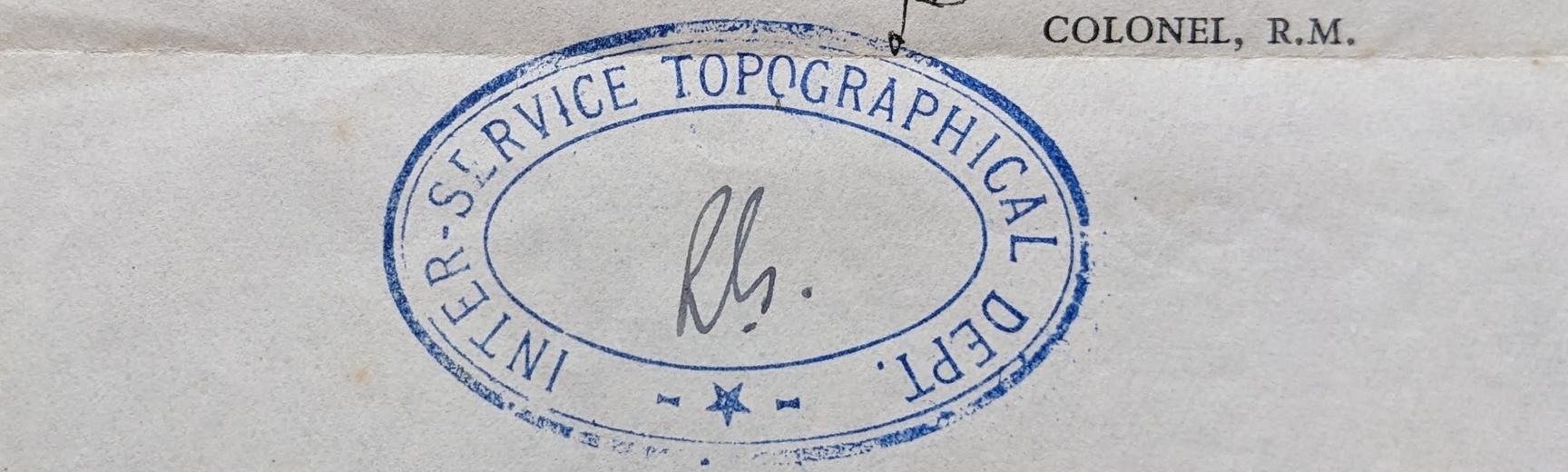

It was Manchester’s fortune to fall within the first category, and it would come to be entirely occupied by the Admiralty, the office of state responsible for the operations of the Royal Navy and the British Empire’s maritime security. In particular, it would become home to a branch of the Naval Intelligence Division (NID). This was the newly created Inter-Service Topographical Department (ISTD), a little-known but hugely important tri-service and inter-Allied outfit. Its purpose was to generate detailed intelligence on the geography, geology, climate, and built infrastructure of locations around the world where British and Allied forces were (or were likely) to conduct military operations, be they Dambuster-style air strikes or vast, complex beach landings such as those that took place on D-Day.

Mansfield Road became one of the most requisitioned parts of Oxford, the take-over of its buildings transforming it into a veritable intelligence quarter of a city packed with war-related activity and alive with the comings and goings of military personnel, civil servants, and civilians engaged by ministries and the armed forces. The School of Geography (SOG) was requisitioned by NID in spring 1940, and the growth of activities relocated there from London led to the takeover of Manchester the following year. Neighbouring Mansfield College had been bagged by the Admiralty and the Government Code and Cypher School (Bletchley Park) as early as August 1939, and parts of its grounds were to be given over to huts accommodating ‘overspill’ activity from Manchester and SOG. New College’s Old Library was also directed towards this purpose, as was part of Balliol College sports ground on Jowett Walk, ‘The Master’s Field’, where huts also sprouted. That wasn’t the end of it: rooms in the Ashmolean were obtained for the accommodation of draughtsmen and mapmakers working for NID units in Manchester and SOG. Their activities also encompassed extensive facilities for map and image production in the New Bodleian, while their prolific output of secret maps, plans, and bound books led to an intimate relationship with Oxford University Press. All told, Colonel Sam Bassett of the Royal Marines, Superintendent of ISTD, had quite an empire to run, and he did it from a desk in Manchester College.

War comes to Manchester

As early as October 1938, the College’s House Committee was discussing air raid precautions and approving the purchase of fire buckets and sandbags. A year later, news was received from the Ministry of Labour that students of theological institutions were to be classified as belonging to a reserved occupation, and would therefore be spared conscription while at their studies. From the start, Manchester was keen to ‘do its bit’, the Principal Reverend Robert Nicol Cross offering the Hall, JCR, and lecture rooms for officer recreation, an offer not taken up though considered by the headquarters of an anti-tank regiment. Olive Jacks, wife of former Principal Lawrence Jacks, suggested that the College should devote its buildings to work of ‘national usefulness’, and an emergency sub-committee comprising the Principal, Bursar, President, Chairman, and Librarian was formed to deal with any applications which might be made for use of the buildings. In October 1939 the Warrington Window and the Chapel window overlooking Mansfield Road were boarded up as a precaution against bomb blast and splinter damage. In June 1940 the Arlosh Hall was opened as a rest room for members of the forces and their friends at weekends. That December, oil paintings were stored in the Chapel vestibule, and the stained glass in the Chapel and the Library was wired with expanded metal, while normal windows were screened with adhesive netting in case of blast damage. As part of a city-wide and University-wide drive, moved along by the Registrar, the iron railings were removed from the Arlosh Quad to support the ‘scrap metal’ appeal.

Plans to turn verdant quads into patriotic potato patches as part of the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign were thwarted when rubble was struck less than a spade down, and it was to be a full two years after war broke out before the College received its marching orders. These came on 17 October 1941, when the Ministry of Works wrote to the Principal explaining that ‘the whole of Manchester College, Oxford, including the Arlosh Hall’ was to be requisitioned. Initially, ‘the Chapel, Main Library, Kitchen and pantry, College Domestic Flat and the Hostel adjoining the College’ were to be left in the hands of the College authorities, something of a ‘share’ arrangement developing as College activities continued in some parts of the premises. But as the House Committee minutes show, College activities were increasingly squeezed into smaller spaces, and the requisition orders grew. The Library, though not requisitioned, was let to the military, its books moved to the Hostel and the New Bodleian. Then, the domestic facilities were taken over, as well as rooms in the Hostel. The enthusiasm that had been prevalent at the start of the war waned as the practicalities of requisition made themselves felt. Much of the correspondence, between College authorities and the military occupiers and Office of Works, was concerned with thing such as rates, rent, utility bills (who was responsible for what), times for lunch and dinner, and compensation for tutors using their homes as office space. As the Principal wrote,

‘requisitioning, like other vices, grows by what it feeds on, and the Ministry of Works commandeered both quads and the tennis court. The lawns have been submerged under a mushroom growth of white huts and sooty outpourings’.

The requisition order extended to the College grounds, including the tennis court (on which secret papers were regularly incinerated), the vegetable garden, garden tools, and the fruit trees. Indicative of the quibbling that attended requisition as the College tried to rub along with the military, the Principal enquired as to whether the College could harvest the produce of the fruit trees. The Ministry’s ‘helpful’ suggestion was that he might seek to buy it back through the District Surveyor’s Department. A row of garages off Saville Row owned by the College was also taken over, though one occupant, Dr C. Noel Davis of 28 Holywell Street, was allowed to retain usage once he explained that he was covering for a young GP who had joined the forces, and therefore needed to be able to drive around the city attending patients. In addition, he explained, he was a member of one of the ‘Air Raid and Mobile Surgical Teams, appointed in connection with the Radcliffe Infirmary and Wingfield-Morris Hospital, for the care and treatment of Air Raid casualties’.

The interiors of College rooms were altered by Manchester’s new occupants, the Library, for instance, emptied of books and equipped with chart racks, filing cabinets, chart presses, and drawing tables. The Principal described workmen putting up black-outs made of wooden frames and ‘rubberoid’ and installing telephones throughout the buildings. For security, given the highly secret nature of the work (those working in Section A didn’t know what those working in Section B, located in an adjacent hut, were doing), all College doors were fitted with Yale locks. Sentries monitored arrivals and checked passes in the entrance hall. An air raid shelter protected by sandbag revetments was established in the refuge beneath the Chapel, and the College housed water pumps in case of fire.

Tutors were moved out of their rooms: Nicols Cross and the tutor-librarian, Reverend Raymond Holt, took tutorials in their own homes, and Reverend Professor D. C. Simpson, Oriel Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture, in his Oriel rooms. Tutor Reverend L. A. Garrard worked from a small room adjoining the requisitioned Bursary, and mid-week services for the students were conducted at Holt’s house. An inspection by the Security Department in December 1942 objected to students walking through the corridors where, owing to an overflow of ISTD staff, ‘a lot of work has to be done’. Bassett told the Principal that it was ‘obviously impossible and would be silly for the girls to cover up maps, etc, when someone passes’. In May 1943, with the number of female staff rising, Bassett was obliged to approach Nicol Cross on the ‘somewhat delicate’ matter of ladies’ lavatory accommodation, requesting access to the toilet by the Library (eventually a new one was built in the Tate Quad).

To increase workspace, single-storey huts were constructed in the Tate Quad and the Arlosh Quad. One of these austere buildings, housing the Norwegian Department of Section B, gathering and processing intelligence for military operations in Scandinavia, was described as a ‘single long room with a jungle of writing tables, drawing boards, archives, map drawers, bookshelves, dressboys, chairs and stools’. Long tables ran along the inner walls, large maps of Norway spread across them, with the section head’s table at the far end surrounded by telephones as well as a scrambler. The hut and its chilly concrete floor were inadequately heated by two coal-burners, and here, seven days a week, laboured twenty-five people, including Finn Dahl, cousin of Roald, and Wolmer Marlow, governor of Svalbard (Spitsbergen).[3]

Rev. Robert Nicol Cross was Principal 1938-1949

The Inter-Service Topographical Department

ISTD was a branch of Naval Intelligence that produced, among other things, detailed geographical and geological information for the use of planners in British and Allied headquarters and the commanders who executed their plans on the ground.[4] The context of its creation was the impoverished state of British intelligence on the places where it was going to have to fight once Europe fell to the Nazis. It encompassed Naval Intelligence Division (NID)5 and NID6. NID5, formed early in 1940, employed teams of geographers in Oxford and Cambridge to produce detailed, long-range information on all aspects of locations where military operations were likely to take place. Among other things, this led to the production of the enormous, 58-volume-long Naval Intelligence Handbooks series, a feat that still ranks as one of the greatest achievements of academic geography. It took over SOG in October 1940, before, together with NID6, expanding to Manchester and beyond. By the time of the Normandy landings, NID6 employed 750 people.

NID6 began life in May 1940 with Colonel Bassett and the University College Oxford classics don Frederick Wells working out of a disused toilet at the Admiralty. Like NID5, it was formed when it was became evident that Britain lacked accurate intelligence about areas where its forces were operating, such as Norway, or likely to operate as the war developed. Campaigning in these areas was likely to involve hazardous amphibious operations featuring air, land, and maritime forces. NID6’s job was to produce topographical – or terrain - intelligence for strategic and tactical use when requested to do so by military planners. Though controlled by the Admiralty, it served all of the armed forces as well as Britain’s allies, coming to embrace officers and civilians not only from Britain but also from America, Holland, and Norway.

Publicity photograph of the many packages received following the BBC appeal for postcards and photographs.

Much of ISTD’s work involved, in Bassett’s words, the study by experts of ‘how to get on a beach and get off it again’, a matter of critical importance for commando raids, the Dieppe Raid, the invasion of Madagascar, the mammoth Operation Torch landings in North Africa, the Operation Overlord landings in Normandy, and planned landings in occupied Malaya. This required the work of a host of specialists, in soil and sand, water tables, tides and currents, the weather, mining, engineering, and the built environment. Data was derived from a range of sources, including books and articles (in plentiful supply in Oxford), aerial photo reconnaissance flights from nearby Oxfordshire airbases, information provided by servicemen inserted into enemy-held territory by small boats launched from naval vessels (including submarines), photos and information provided by private companies with overseas interests, a contact registry of people known to have recent experience of living in or visiting overseas locations, and the ten million postcards and holiday snaps, sent by members of the public in answer to an appeal broadcast by the BBC, that came to form part of the Admiralty Photographic Library.

ISTD personnel working in Manchester College provided intelligence for the ‘Dambusters’ raid, working out the flow of feeder rivers and the maximum capacity of the water before overspill, a botany expert using the state of vegetation shown on aerial reconnaissance photos of the dam to assess when it was at its highest. ISTD also identified a suitable Scottish loch for practice runs. In another famous operation, ISTD provided intelligence for the strikes that eventually sank the German battleship Tirpitz (constructing a full-scale model of the fjord it was hiding in as part of its efforts to instruct the pilots who would conduct the attacks). ISTD was drawn upon by a diverse range of military ‘end users’: it helped direct commando raids, sabotage operations, and targeted air attacks; it identified terrain on which gliders might attempt safely to land, and onto which paratroops or supplies might be dropped; it identified areas where airfields might best be established, or where fresh water might be found; and it helped those planning the reconstruction of German oilfields on their capture.

The ISTD’s Fire Vulnerability Section produced hundreds of brightly coloured and information-laden maps, covering conurbations across the world where the Allies were likely to drop bombs or deploy land forces. It established which parts of cities were most susceptible to firebombs, targets where incendiary or ‘blockbuster’ bombs could be used to best effect (no point dropping a fire bomb on an area not likely to catch fire), and the fire vulnerability of buildings and infrastructure in the ports and inland towns and cities where Allied forces would mass as they invaded Europe and fought towards Berlin. This not only aided Allied targeting of towns and cities under enemy occupation, but provided valuable information once they had been captured – where for example, not to store ammunition in case of German bombing or shelling, where fresh water could be found, and where it might be safest to locate headquarters.

Detail of the work conducted at Manchester College

There can be no doubt that ISTD, anchored throughout the war at Manchester College, produced a range of intelligence outputs that were strategically vital to British and Allied operations. The contribution to the D-Day landings naturally stand out, but it is in the detail of smaller operations that the remarkable nature of the work involved is brought to the fore. One such was a raid on German ships anchored at the French port of Bordeaux, made famous in the film The Cockleshell Heroes. The attack was to be conducted by canoeists, who would enter the Gironde estuary, find their way to the mouth of the Garonne River, canoe up it, and attach limpet mines to their targets. This entailed paddling eighty miles. The task of ISTD was to provide as much detailed information as possible to help the brave souls who had volunteered to undertake this daredevil, and potentially suicidal, enterprise. ISTD staff at Manchester furnished information on tides and currents and pinpointed safe hiding places where the men could lay up during daylight hours. To do this, more than 2000 ground and aerial photos of the region were studied and over 600 silhouettes composed to enable the canoeists to identify their position while moving under cover of darkness, working out heights of landmarks and natural features, and even providing information on the distinct smells of the region, emanating, for example, from a brewery and a chemical factory.

The second example comes from Hedin Brønner, one of the Norwegians working in Section B. His job was to produce marked maps and detailed images of targets to be attacked, constructing mosaics made from glued together photos in order to do so. ‘A target at Skien river is to be attacked by Mosquito planes from low altitude’, he wrote of one such operation. Only the day before, British photo reconnaissance aircraft had flown over the area, and now, as a result, Hedin had before him two heaps of photos, rushed to Manchester when aircraft landed at their Oxfordshire base following sorties over Norway. Hedin then put the photos under a stereoscope, a device that allowed the viewer to see a 3-D image and that was essential if accurate intelligence on heights, depths, and features was to be generated.

A publicity image taken by Peter Bradford of staff from the ISTD. The piece of equipment in the middle, the stereoscope, enabled a set of overlapping images to be viewed in 3-D.

Now I look down through the lenses for the first time. For a few seconds my eye muscles are opposing, then the terrain jumps up towards me in three dimensions, so suddenly that I jump. There is snow on the ground, all mixed up colours and tints have gone away. And there is sunshine. Trees and houses pop up so alive that you want to touch them with your finger, and by the shadows on the snow you may study the vertical forms as if you were standing there yourself. One of the most important things we find is a cable which is stretched over the river between two tall masts, and on the mosaic this is marked by white ink and a warning text added [for the benefit of the pilots who would deliver the attack at low altitude].

War’s end

VE Day 1945 was marked by a thanksgiving service in the Chapel. But victory did not bring an immediate return to normal. Like other colleges, derequisitioning took time – until September 1946 in Manchester’s case. Even now, the Nissen huts in its quads were still needed by the military, and then colleges such as Balliol, New College, and Univ argued that they should be kept in order to provide student accommodation, the dearth of which was a University-wide problem as normal activities resumed and a backlog of students came up to begin their studies or continue them following war service. The University, meanwhile, thought the Manchester huts might accommodate a ‘homeless’ institution, the Institute of Statistics being suggested. But the College saw the removal of the huts as a priority; there was an overwhelming desire to get back to normal, and fears that squatters would ‘requisition’ them, as they had those on the nearby Balliol ground.

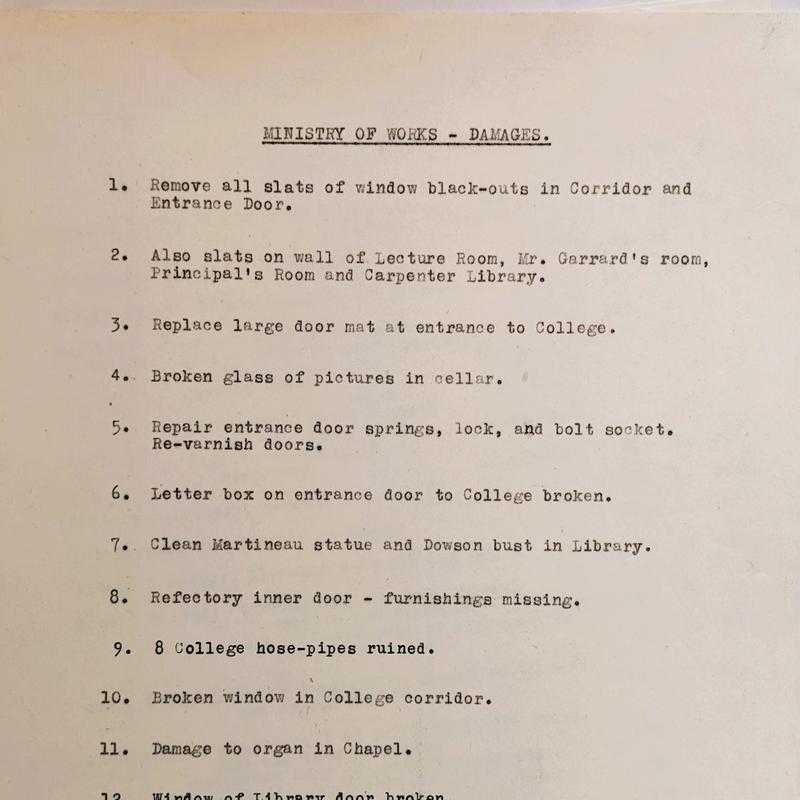

A detailed schedule of ‘dilapidations’ was produced in June 1947 as the College sought compensation for damage and wear and tear (prepared in great detail, as for other Oxford colleges, by the University of Cambridge’s Department of Estate Management and managed by a bursarial committee chaired by the Bursar of St John’s). The Carpenter Library needed reglazing, removal of noticeboards, plugging of holes, new lino, and floor repairs. The mosaic floor in the Library lobby needed repair and in the SCR new brass sash window lifts were required along with corded cleats . The Yale locks needed to be removed, and the cost of a new WC pan for the ladies’ lavatory was claimed. So, too, were repairs to the organ, which had been seriously affected by the Admiralty’s persistent overheating of the Chapel. As late as March 1947, the Principal wrote that there was still lots to be done, including the planing and polishing of the Library and Hall floors, the cleaning of stonework, and the breaking up of the concrete foundations of the now-removed huts, to be followed by the restoration of the lawns.

A plaque in the entrance to the Arlosh Hall, unveiled by Princess Anne in 2014, marks the preparation for D-Day that took place there. It is, perhaps, insufficient testament to the manner in which the whole of Manchester College was involved in the war effort, and the extraordinary nature and great importance of what took place there.

Various lists exist that set out the condition of the College following ISTD's departure after the end of the War.

[1] Ashley Jackson is Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College London and a Visiting Fellow of Kellogg College Oxford. Kate Alderson-Smith is Fellow Librarian at Harris Manchester College Oxford. Together with Amanda Ingram, Archivist at Pembroke College Oxford and St Hugh’s College Oxford, they gave a talk at the Kellogg College-Bletchley Park Week 2023 featuring Harris Manchester’s war experience. See ‘From Geographical Intelligence to Major Head Injuries: Oxford Colleges at War’, available via YouTube at https://youtu.be/ZEkRGKS9D54

Jackson’s study of Oxford's War 1939-1945 will be published by Bodleian Library Publishing in 2024. The material here relating to HMC is drawn from the College’s own archives, particularly: ‘General Committee Minutes, 1938-1943’; Annual Reports, Letters, 1940-47; MS.1 World War II, MS.2 World War II, MS.3 World War II, and MS.4 World War II. The General Committee met around five times a year and consisted of the Trustees and key staff. Various sub-committees reported to it, including the House Committee.

[2] For an excellent overview of the war’s impact on the University and colleges, see Paul Addison, ‘Oxford and the Second World War’, in Brian Harrison (ed), The History of the University of Oxford, volume 8, The Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). For an emphasis on the city and the county, see Malcolm Graham’s splendid Oxfordshire at War (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1994). On the work of ISTD, see Sam Bassett, Royal Marine: The Autobiography of Colonel Sam Bassett, CBE, RM (London: Peter Davies, 1962). For an intriguing recent treatment of the ISTD, see Alistair Black, ‘Information, Topography and War: Information Management in Britain’s Inter-Service Topographical Department (ISTD) in the Second World War’, in Toni Weller, Alistair Black, Bonnie Mak and Laura Skouvig (eds), Routledge Handbook of Information History (forthcoming, 2024).

[3] The population of the settlement there was evacuated by the Royal Navy in 1941.

[4] The work of the Inter-Service Liaison Department has been examined in several excellent articles in geographical, cartographical, engineering, and military journals, a prominent name in the field being Edward Rose. The College Archives hold copies of the most important articles. For the history of the Naval Intelligence Department, see Anthony Wells, ‘Studies in British Naval Intelligence, 1880-1945’, Ph. D. Thesis (King’s College London, 1972) and John Godfrey, ‘The Naval Memoirs of Admiral J. H. Godfrey’, unpublished manuscript (copies held in the library of the Joint Service Command and Staff College, Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, Imperial War Museums, and the National Maritime Museum).